What a strange 2020 it’s been so far. For the satellite industry. For the broader space industry. For the entirety of humanity. When we rang in the new decade just a few months ago, no one could have foreseen the enormous changes that were coming to the way we live, work, and geek out about space.

But indeed, we now find ourselves in the midst of a rapidly-changing world, and one that is, as of May 2020, still largely shut down. One of the places that is most “back to normal,” however, is China, and its space industry is no different. My vantage point for this year has been the Fragrant Harbor of Hong Kong, but with daily contact with my business partner in Beijing and other colleagues elsewhere in China. From this slightly odd vantage point (Hong Kong has very little space industry of which to speak), I have been able to watch what has been perhaps the most dynamic half-year we have yet seen in China commercial space.

The Space Industry in China Pre-COVID

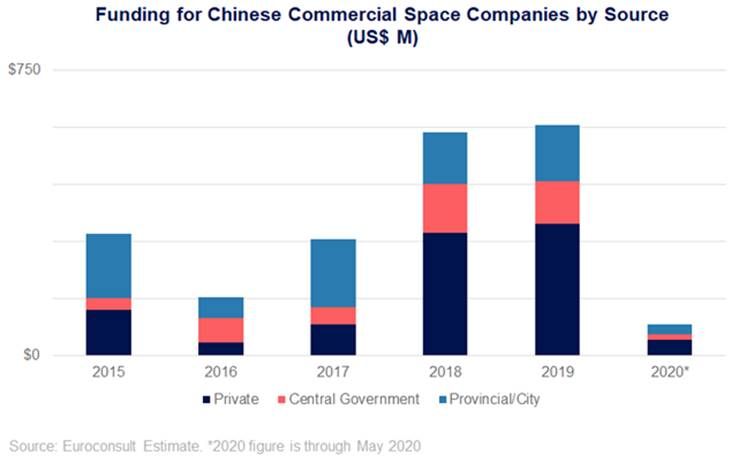

The Chinese space industry has been experiencing the beginnings of what may be a commercial renaissance of sorts, with more than 100 commercial companies having been founded since 2014, at which time the Chinese government relaxed restrictions on private investment into certain parts of the space sector. As part of our China Space Industry Report, Euroconsult tracks Chinese commercial space funding, and we calculate that since 2014, more than RMB 13 billion (US$ 1.9B) has been invested into commercial space companies in China, with around half of this figure coming from private funding (i.e. Chinese VCs and the like). This funding started to trickle in 2014 (around US$2 million of funding that year), and up to 2019 continued to grow, reaching nearly RMB 4.5B (US$650 million) last year.

Technologically, pre-COVID, we saw over 100 companies founded, roughly in two generations. Companies in the first generation, those founded between 2014-2016, have tended to focus on systems-level technologies, such as rockets. Companies in the second generation, those founded since 2017, have more often focused on sub-systems technologies, such as rocket engines (though several, such as Galactic Energy, founded in 2018, have focused on systems-level). Going into 2020, several launch companies were planning their first launch of a given rocket, several constellations were planning to launch their first satellites, and in general, many big plans were made. Which begs the question—how has that gone?

Technologically, pre-COVID, we saw over 100 companies founded, roughly in two generations. Companies in the first generation, those founded between 2014-2016, have tended to focus on systems-level technologies, such as rockets. Companies in the second generation, those founded since 2017, have more often focused on sub-systems technologies, such as rocket engines (though several, such as Galactic Energy, founded in 2018, have focused on systems-level). Going into 2020, several launch companies were planning their first launch of a given rocket, several constellations were planning to launch their first satellites, and in general, many big plans were made. Which begs the question—how has that gone?

Which Brings us to 2020

2020 in the Chinese space industry has been unusual for sure. With the entire country shut down for most of February, March, and parts of April due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many industries have slowed down, space being no exception. However, slowdown has not meant stoppage, and indeed, there are still a lot, lot of things happening in the space industry in China at the moment.

In the last six months including the last weeks of 2019, fundraising has slowed, but not stopped. The last big round pre-COVID was Landspace’s C-round in December 2019 for RMB 500M (US$ 71 million) from Country Garden Ventures. Since the beginning of 2020, we have seen six rounds of funding, with five of them occurring since March. This has included two rounds by satellite manufacturer MinoSpace totaling an estimated RMB 100 million (US$ 14 mil.), and one round by Commsat completed earlier in May for RMB 270 million (US$ 39 mil.), with the round valuing the company at RMB 2.1 illion (US$ 300 million). That is to say, despite the slowdown, funding has continued to flow. Total funds raised in 2020 as of mid-May was somewhere between RMB 500 million and RMB 640 million, around 15% of 2019 levels. This is partly, however, explained by the aforementioned several large rounds occurring just before 2020, which is to say that companies such as. Landspace (RMB 500 million in December), Galactic Energy (RMB 150M in October 2019), Galaxy Space (~RMB500-700 million in September. 2019), and others raised a lot of money shortly before the crisis.

Ultimately, while 2020 has unquestionably seen a slowdown in funding, it has not been a complete stoppage. Indeed, the past several weeks have seen, if anything, a major acceleration in funding, due to a major ruling by China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC).

“New Infrastructures”

China’s NDRC is a very powerful entity. In an economy where the majority of productivity is still controlled directly or indirectly by the state, and where there exists an organization that is only tasked with managing US$ 26 trillion in state-owned enterprise (SOE) assets (SASAC), the NDRC is the group that influences which industries will “develop” and “reform”, and how that will happen. Develop in this context would mean develop economically, i.e. grow. Reform is a somewhat less straightforward term, but would generally mean allowing industries primarily controlled by SOEs to allow more private competition, more foreign investment, or otherwise proposing structural changes or these industries. So, given the size/influence of the state within China’s economy, and the subsequent influence that the NDRC has over the behavior of the SOEs, any decision made by the NDRC carries significant weight.

For this reason, when the NDRC announced in April 2020 that they were adding satellite internet, internet of things, and 5G to their list of “new infrastructures”(新基建), I felt it might open the floodgates. The “new infrastructures” list, as the name suggests, is a list of types of infrastructure in which the NDRC encourages investment/development. Within a week of the announcement, China Unicom Airnet—the satcom subsidiary of China Unicom—announced 4 new satellite products, 3 of which were broadband-related, specifically mentioning the NDRC ruling. Roughly 10 days after that, Commsat announced a RMB 270 illion(US$ 39 mil.) round of funding, with the announcement mentioning the NDRC ruling, and with the money specified as being earmarked for building a satellite manufacturing line for communications satellites in line with the new infrastructure plan.

The National People’s Congress is a major political event in China. Originally scheduled for March 2020, it was postponed until May due to COVID-19. One of the attendees will be Lei Jun, CEO of Xiaomi, a major tech firm, and a major investor in Galaxy Space--a proponent of space more broadly. In this correspondent’s opinion, Lei Jun is the closest thing that China currently has to Elon Musk, so his word may carry some weight. As well, despite being relatively young, he is a longtime Beijing heavyweight, having made his fortune as a tech whizkid at a formerly state-owned software giant Kingsoft before branching out into VC and other businesses, most notably Xiaomi. He is now worth US$12 billion. Kuaizhou-1A rocket commemorating first responders

Prior to the Congress, Lei Jun published a document with four main proposals, including incorporating satellite internet as a key strategic emerging industry in China’s 14th Five-Year Plan, reform domestic satellite frequency coordination and adopt more international standards, further liberalize access of private enterprises, and establish a large-scale national-level development fund. If any of Lei Jun’s proposals come close to being adopted, it would be significant. We will find out to some extent. in the coming weeks, but it is also possible that the Congress will involve the planting of seeds of reform that may come about later on. Either way, the atmosphere in Beijing will be exciting, with the NDRC ruling fresh in people’s minds, and with extraordinary feats being accomplished by Starlink….of which the United States military would be a major user. In short, from a policy perspective, 2020 has thus far been about as exciting as policy can get, and amazingly, we might be at just the beginning.

Finally, What are the Companies Actually Doing?

Now that we have covered all the exciting stuff like policies and financing, we arrive at the tedium of launching rockets. Similar to funding, 2020

|

| Kuaizhou-1A rocket commemorating first responders from Wuhan. |

has thus far seen a slowdown, but far from a stoppage in launches. Most noteworthy was the launch in May 2020 of a Kuaizhou-1A rocket from Expace, with a payload of 2x satellites for CASIC’s Xingyun narrowband constellation. Both Expace and LEObit Technologies (the operating company for Xingyun) are headquartered in Wuhan, and the launch was indicative of the speed at which the city has seemingly sprung back to action.

The rocket was decorated to commemorate the first responders to the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, and was also sponsored by Guangqi, a major car company. The launch put the two ~200kg satellites into orbit as the first two of the 80-satelltie constellation. Both companies will be utilizing the Wuhan Aerospace Industrial Base, a major initiative that will be coming into operation during 2020 and which includes rocket manufacturing facilities for 20x Kuaizhou rockets per year, and a satellite manufacturing line for ~120 smallsats per year (assumed to be ~200kg i.e. “Xingyun-sized” satellites).

Apart from the successful launch, Expace had another eventful moment in 2020. April 1 is “April Fool’s Day” in the west, but in China it is slightly different, insofar as it is “Crazy Day”. That is, you can do crazy things that may or may not be jokes. With this in mind, Expace conducted an online auction for a Kuaizhou rocket launch, and the winning bidder offered US$ 5.6 million. Rumors were later confirmed that the bidder was Charming Globe, a large Earth Observation (EO) constellation operator and service provider. More importantly, the online auction was a massive viral hit, generating over 500 million searches and several million people watching live. I recall my first space conference inside of China in 2017, at which time they live-streamed the event with many people online sending in questions. It occurred to me then that space in China today is probably a bit like space in the United States in the 1960s—that is to say, it’s pretty darn popular. The fact that half a billion people searched for a rocket auction is yet another example of the apparent mass popularity of space in China today.

Other major events in China in 2020 have included the launch of Galaxy Space’s first satellite. Galaxy Space is likely China’s most well-funded private constellation, having likely raised more than US$200 million, at a most recent valuation of RMB 5 Billion (US $700 million). The company plans to launch a LEO comms constellation of several hundred, and eventually more than 1000 satellites to serve 5G, IoT, and satellite broadband. If those three things sound familiar, they should—they are the three things added to the new infrastructures by the NDRC earlier this year. And the main investor in Galaxy Space? Our friend Lei Jun. What a time to be in China.

Other activities among Chinese space companies in 2020 have included the successful first launch of the Long March-5B, a variant of the Long March-5 heavy lift rocket. The LM-5B involves removing a 2nd stage and adding larger payload to LEO. The launch also involved the non-crewed test of a crewed spacecraft, with the spacecraft orbiting. For several days then returning to earth. The rocket success is a major step for China’s space program, insofar as the LM-5B will be used for the Chinese Space Station and other major missions.

Conclusion—What a Half a Year

Incredibly, we have only scratched the surface of the half-year that was in Chinese space. Despite a pandemic and ensuing total shutdown, the industry moved along at a solid pace, and we have seen projects continue to move forward. The second half of the year may, if anything, be even more eventful after seeing the full impact of the NDRC decision, and the ongoing Congress. Until then, you can find my LinkedIn (where I regularly publish short updates on China space) using any search engine and searching the hashtag #ChinaSpaceGuy

--------------------------------------------

Blaine Curcio is the Founder of Orbital Gateway Consulting. He’s an expert on the commercial space and satellite industries with a focus on the Asia-Pacific region. He can be reached at: blaine@orbitalgatewayconsulting.com