As we’ve said for quite some time, the satellite communications market in China has historically been a pretty vanilla affair. On the Geostationary (GEO) side, the state-owned China Satcom runs an effective monopoly on the provision of satellite services, occasionally buying additional capacity from its partial subsidiary APT Satellite, and from foreign operators. On the non-GEO side, we’ve seen limited activity from state-owned China Satellite Networks Limited (China SatNet), a centrally-controlled state-owned enterprise (SOE) founded in 2021 with the purpose of deploying a “Chinese version of Starlink”.

2023 has seen some changes in both GEO and NGSO satcom, with better-defined and somewhat bigger ambitions in the GEO space coming from China Satcom, and with significantly more dynamism coming in the NGSO space.

|

Bringing China into the VHTS Era

One thing that has not changed over the past couple of years in the Chinese satcom market is the nature of GEO competition: China Satcom maintains an effective monopoly. Up until recently (and even now to some extent), this has limited their incentive to innovate, however the past couple of years have seen too much high-level support for satcom, and they’ve had no choice. 2023 has seen this crystalize, with a few interesting announcements and events.

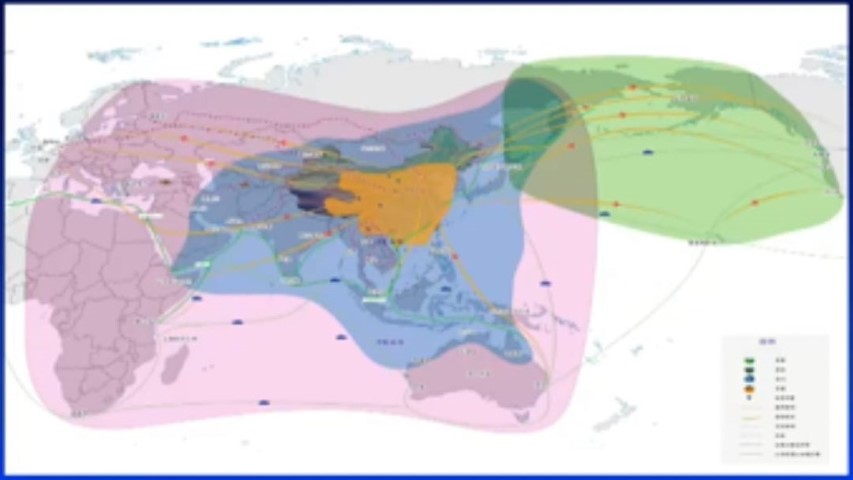

First, in February, the ChinaSat-26 satellite was launched, representing China’s first satellite of ~100 Gbps capacity. With coverage extending from parts of Eastern Russia to the Horn of Africa and from Australia to Central Asia (blue coverage map below), the satellite represents by far China Satcom’s largest on-orbit to date (next largest being ChinaSat-16, with 20 Gbps). With nearly 2 Gbps per beam and capabilities of bringing 450 Mbps of capacity to any single user terminal, ChinaSat-26 represents a major improvement in China Satcom’s GEO-HTS offerings.

"...One thing that has not changed over the past couple of years in the Chinese satcom market is the nature of GEO competition: China Satcom maintains an effective monopoly...."

With that said, this year also saw China Satcom announce an even bigger satellite, ChinaSat-27. Planned for 2025, ChinaSat-27 will bring 300 Gbps of capacity to most of Africa and Eurasia (pink coverage map on the above image), with capabilities of bringing 1 Gbps to any single user terminal. As noted by a talk from China Satcom’s Peng Tao at the 2023 China Radio Conference in September, ChinaSat-27 is a partially flexible GEO-HTS, bringing China to about the same level as ViaSat-2 or Jupiter-2 in terms of large GEO-HTS technology.

Figure 1: ChinaSat Current and Future Coverage, including ChinaSat-16 (orange), ChinaSat-19 (green), ChinaSat-26 (blue), and ChinaSat-27 (pink).

In terms of total fleet capacity, in December this year, we saw an announcement from CASC that China Satcom would exceed 500 Gbps of total capacity by the end of the 14th Five-Year Plan period (i.e. end of 2025). China Satcom’s HTS fleet will use Ka-band, with APT Satellite of Hong Kong and its sister company, APT Mobile Satcom of Shenzhen using Ku-band on their HTS fleet. While much of this capacity would be covering China, as the coverage maps above show, a lot of it would be over the rest of APAC, Africa, and parts of Europe. Clearly a couple of major target markets would be Chinese airlines and Chinese maritime vessels, and in the medium-term, potential GEO/LEO integration with a Chinese constellation. For the next several years, though, it seems that there will be a lot of China Satcom capacity coming into markets where there is not immediate demand that China Satcom can serve. Markets from the Pacific Islands to Africa may find additional capacity being dumped at highly competitive prices.

NGSO Broadening Out Beyond Just the State

Up until 2023, it seemed a lock that China’s large Non-Geostationary Orbit (NGSO) constellation project would be developed by one company, and one company only: China Satellite Networks Limited (China SatNet). A centrally-controlled SOE established by the State Council in early 2021, the company’s sole purpose for existence was to develop China’s answer to Starlink. And for several years, they have done not so much, beyond a disciplinary investigation and some moderately impressive progress on a headquarters building in Xiong’an, the newish capital district being built to the south of Beijing.

And so it is perhaps not surprising that during 2023, we have seen a change in tune with regard to NGSO constellations. Notably, it seems there is more room for other players beyond China SatNet, with evidence appearing from both a top-down and bottom-up perspective. Looking top-down, we saw more government support in 2023 for constellations that were not China SatNet. The most noteworthy pieces of support were several Shanghai Government announcements related to satellite internet, which specifically called for supporting the G60 constellation (Chinese NGSO broadband constellation that brings together many of the Chinese parts of the former KLEO Connect) and the Smart SkyNet constellation (“Chinese version of O3b”, i.e. MEO comms constellation).

Figure 2: Solar Panel on Lingxi-03 Satellite, Built by Galaxy Space.

Such explicit support for a constellation that is not China SatNet was a marked change of pace, and it was followed by more intrigue coming out of China. In August of this year, we saw multiple new ITU filings for Chinese NGSO broadband constellations, with two in particular standing out. First, a 1,804 “Black Spider Constellation” from Galaxy Space, and second, multiple constellations filed for SAILSpace, a Shanghai entity affiliated with several former Chinese KLEO Connect shareholders. In a final indication of top-down support for opening up to the private sector, in October we saw an announcement from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) titled “Opinions on Innovating the Management of Information and Communications Industry to Optimize the Business Environment” (what a mouthful). In short, this called for the opening of the telecommunications business to private capital, and to promote the reform of the satellite internet business in steps and stages. Or, change is coming, and while it might come slowly, it is coming nonetheless. Companies, take note.

Looking from a bottom up perspective, we continued to see progress from commercial NGSO companies developing their technologies. Most notably, Galaxy Space debuted a stackable satellite that mimics Starlink’s design in an effort to fit dozens of satellites on a single rocket, as well as a satellite with very thin, foldable solar panels. At the same time, the G60 Industrial Base near Shanghai, affiliated with the aforementioned constellation of the same name, has continued to progress, and both Galaxy Space and SSST have made efforts to branch out to international markets offering scalable NGSO satellite communications solutions.

Ground Segment

China’s VSAT terminal manufacturers also made significant strides in 2023. The standout performer, particularly from an international perspective, was Starwin, a Chengdu-based VSAT manufacturer that appeared at countless international conferences in 2023 including Euroconsult World Satellite Business Week and Asia Tech X Singapore. More tangibly, the company also achieved certification with Hispasat’s network, this coming a few years after similar collaboration with Intelsat.

With a suite of flat-panel electronically-steered antennas, Starwin fashions themselves as a competitor to the leading FPA manufacturers in the United States and elsewhere, and their track record in 2023 shows they are not kidding. In addition to fairly traditional FPAs, Starwin has developed a terminal specifically focused on connecting UAVs to satellite, and then allowing the UAV to broadcast connectivity, like a mobile 4G station in the sky. Other VSAT manufacturers including Cowave have broadened their international reach in 2023, though from a lower starting point. The company created a YouTube channel, for one, to advertise its various VSAT wares to a broader, more international audience.

China’s Satcom Sector Moving Forward

By all accounts, China’s satcom sector today is a largely domestic affair. China Satcom sells satellite capacity to Chinese state-owned broadcasters, state-owned telcos, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and the state at large (are you sensing a theme here??). The offerings tend to be relatively old tech, and apart from the occasional exception like APT Satellite doing a good business in Indonesia, the solutions are confined to the Chinese market.

With a suite of flat-panel electronically-steered antennas, Starwin fashions themselves as a competitor to the leading FPA manufacturers in the United States and elsewhere. Pictured here is their portable Ku-Band flat panel antenna.

This is going to change. By the end of 2025, China Satcom will have more GEO capacity than any other satellite operator in Asia-Pacific, with the possible expectation of ViaSat if their 1 Tbps ViaSat-3 APAC launches over the region as planned. As noted, much of this capacity is covering China, but a lot of it is not. By end of 2025, we may also have the beginnings of a Chinese NGSO broadband constellation coming into the market, though the commercial impact would likely not be felt until later in the decade.

Overall, we cannot be sure what the future will hold for the Chinese satcom sector. However, if 2023 was any indication, we should expect to see a future that is more internationally-focused, and with a greater variety of players competing.

--------------------------------------------------------- Blaine Curcio is the Founder of Orbital Gateway Consulting. He’s an expert on the commercial space and satellite industries with a focus on the Asia-Pacific region. He is also an Affiliate Senior Consultant for Euroconsult. Since joining Euroconsult in 2018, he has contributed to a wide range of consulting missions and research reports, primarily covering the satcom sector globally, and broader space industry in China. He can be reached at: blaine@orbitalgatewayconsulting.com

Blaine Curcio is the Founder of Orbital Gateway Consulting. He’s an expert on the commercial space and satellite industries with a focus on the Asia-Pacific region. He is also an Affiliate Senior Consultant for Euroconsult. Since joining Euroconsult in 2018, he has contributed to a wide range of consulting missions and research reports, primarily covering the satcom sector globally, and broader space industry in China. He can be reached at: blaine@orbitalgatewayconsulting.com