The rapid rise of China’s space sector has been well-documented over the past few years. With more than 200 commercial companies having been established since 2014, and with a robust civil space sector providing infrastructural support, the Chinese space industry is fast evolving into one of the world’s most comprehensively capable ones. Dozens of commercial launch startups, vertically integrated earth observation companies with IPO plans, and everything in-between: as is the case in so many industries, “Made in China” is likely to become a commonly heard phrase in the space sector.

With this rise will unquestionably come challenges and opportunities. These will be unique for all companies and industries, but having had a front-row seat to all things Chinese space for more than 5 years, we at OGC can provide an overview based on experience with clients, acquaintances, and other contacts within the Chinese space sector. We will first give a summary of the Chinese space sector and its growth to today, before discussing some of its inherent strengths and weaknesses, and finally opportunities for non-Chinese companies.

Emergence of the Chinese Space Sector

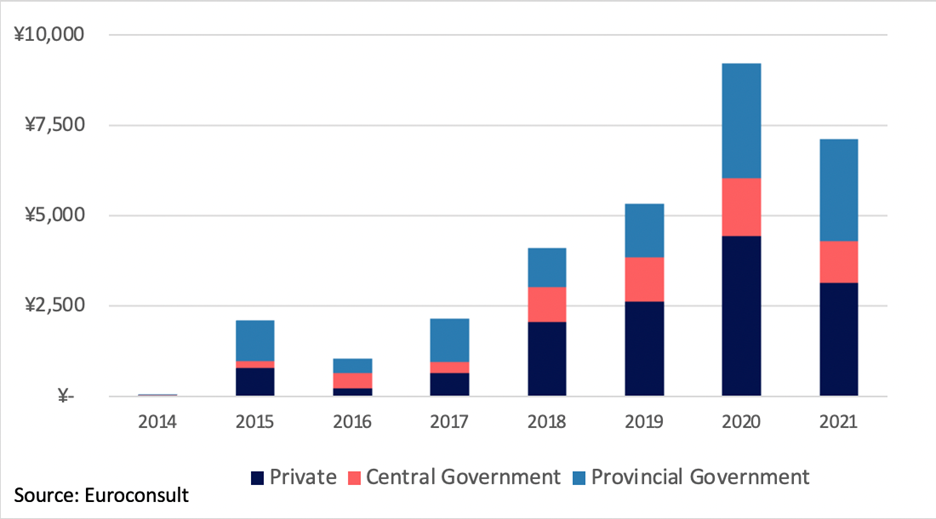

The Chinese space sector was wholly state-owned until 2014, at which time the State Council published so-called Document 60, a proclamation calling for more private investment into areas such as launch vehicles and satellite manufacturing. Initially growth was slow—only a handful of commercial space companies were founded in 2015 and 2016. This was likely in part because of uncertainty about the meaning and extent to which the space sector was really open to private investment. In the ensuing 2-3 years, subsequent government support was published, giving investors and other stakeholders sufficient comfort to start investing into these startups.

|

| Chinese Commercial Space Funding by Source, 2014-2021 (¥M) |

And at least in terms of fundraising, the results speak for themselves. From basically zero in 2014, China saw a peak of more than ¥9 Billion (~US$1.5 Bil.) invested into commercial space companies in 2020, with 2021 seeing a small dip to ¥7 Bil. (though noteworthily, 2020’s biggest round by far was in December with CGSTL’s massive ¥2.46 Bil. pre-IPO round….so annual totals in this case can be misleading). Total investment into Chinese commercial space since 2014 has been an estimated ~¥33 Bil., this according to Euroconsult’s China Space Industry Report.

The nature of companies being founded has evolved since 2014, and we have seen several trends emerge very recently. The first few commercial space companies in China were primarily spinoffs from existing players. The case-in-point would be CGSTL, China’s leading commercial remote sensing company and one of its first commercial space companies, founded in December 2014. While nominally commercial, CGSTL was originally a spinoff from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) Changchun Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics, where the team of researchers had collaborated on remote sensing satellite R&D for more than a decade.

Moving into the late 2010s, we started to see an increasing number of commercial space companies created more organically, although with significant state heritage. Companies such as MinoSpace, Spacety, and Galaxy Space—all commercial satellite manufacturers among other things—were founded by teams combining former employees of the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC; the main state-owned space contractor), the CAS, and non-space sectors. These companies are primarily focused on systems-level technologies (satellites, rockets, etc.), and for the most part have been working to sell into state-owned enterprises, universities, or other government demand. With a certain level of SOE DNA, these companies tend to be somewhat less international than companies of similar size in other space ecosystems. Finally, most of this “first generation” of commercial space startups have some degree of flexibility which can be advantageous in the Chinese context. For example, a satellite manufacturer may also develop capabilities in terminals and applications, because the regulatory future of all three industries is not very clear (better to hedge one’s bets).

More Recent Ongoings

The first 2 years of the 2020s have seen an evolution in China’s space sector. Startups continue to pop up at a rapid pace, but most of the commercial companies founded today are focusing on very specific technologies. In short, it’s hard to compete in launch in China today as there are already ~25 launch companies—it makes no sense to create company #26 in 2022. But, many of the 25 launch companies need suppliers, and it might make good sense to create a company developing liquid methalox rocket engines to sell to all 25 commercial launch companies (and also the state). Jiuzhou Yunjian is a launch startup founded in 2018 doing exactly that. The same phenomenon has occurred in areas such as Hall Effect Thrusters (Yidong Aerospace and Xingkong Dongli, among others), laser inter-satellite links (HiStarlink and Laser Starcom, among others), and general satellite components (iStar Aerospace).

All these newly established commercial space companies exist in a diverse and multifaceted system with many stakeholders. The Chinese space sector has seen several competitive companies emerge, and there will undeniably be many more such companies in the future, aided by further tailwinds of government support at multiple levels. The unique structure of the Chinese space industry means that opportunities and threats need to be viewed with much context, and will vary significantly based on company and vertical.

Perspectives on the Industry: The Good

We’ve already established that China has seen some ~200 commercial space companies created over the past 8 years, having raised some ¥33B with plans to develop technologies, partly in support of a massive and diverse state-owned sector. Put another way: it’s a big freaking market. But as is the case in China, things can be complicated, and recent geopolitical events have certainly not helped to uncomplicate things. Having worked with, among others, foreign suppliers looking at the Chinese market, Chinese suppliers looking at foreign markets, American think tanks studying China commercial space, and just about everyone in-between, we at OGC have just about seen it all in the context of Chinese space.

First, the good. There are an astonishing number of companies, they are willing to try new things, and they are willing to move very fast. Taking the example of Spacety, the Chinese commercial satellite manufacturer has partnered with a number of European component manufacturers to offer on-orbit verification using a Spacety satellite platform as a ride to space. Part of the reason Spacety can win such business is that they launch smallsats very regularly—every couple of months or so—and they offer modular space on these launches. For a European component manufacturer, the option could be to wait 12-18+ months for a European launch slot, which may be the safer bet, or to wait ~3 months for a Chinese launch slot, the perhaps riskier, but also certainly faster option. Commercial companies also have interesting collaboration with the state, with a launch cluster in Southern Beijing being the most obvious example of many startups clustering around one major SOE (in that case, CALT).

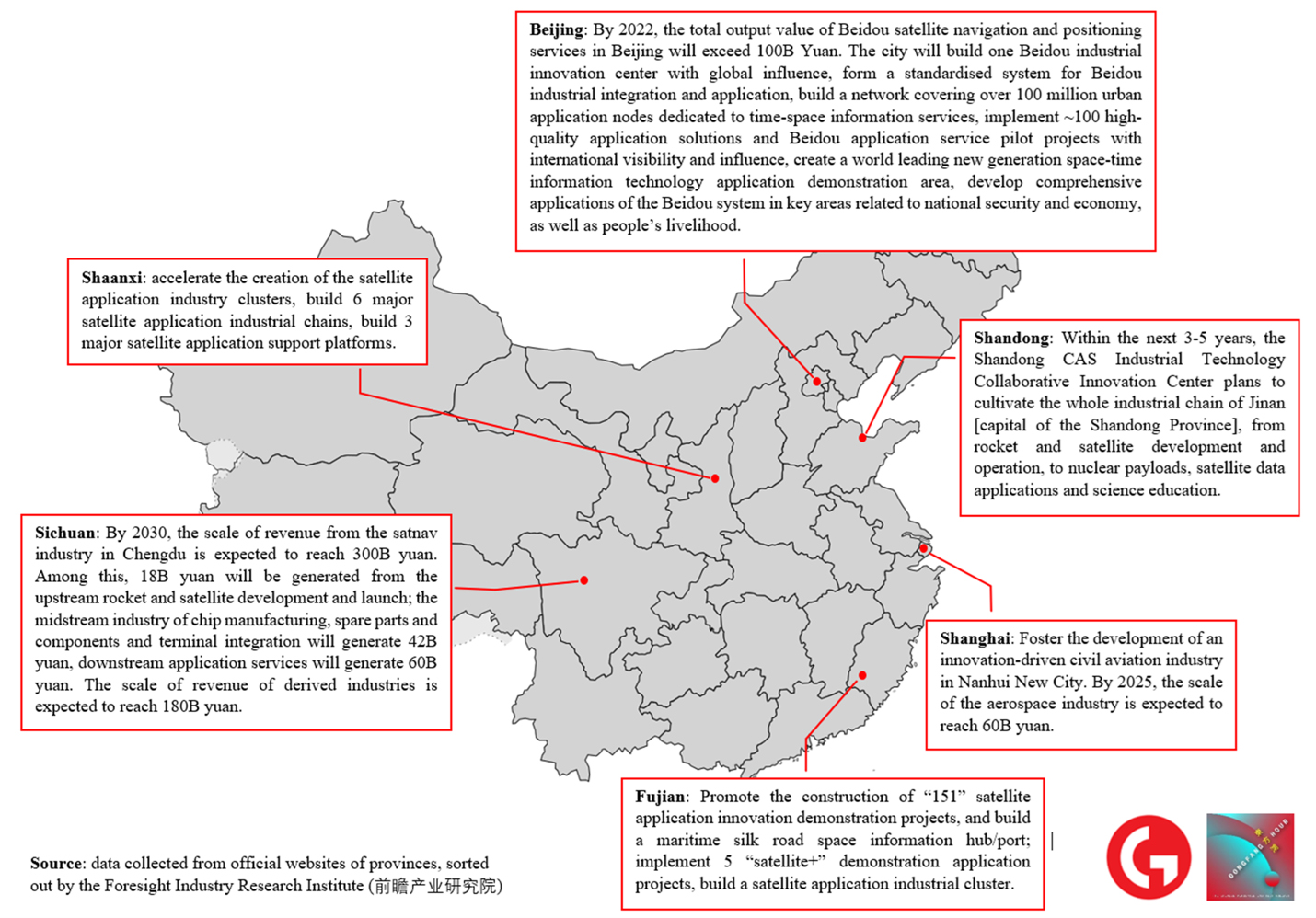

There is also support in the Chinese space sector across several levels of government, including support for international cooperation. At the

|

| Select Provincial-Level Government Policies Pertaining to Chinese Space |

local level, the city of Shenzhen published in July 2021 a list of available subsidies and support measures for companies developing satellite-related technology, which included support for reaching international certification, subsidies for international market access, and subsidies for JVs with foreign companies in related industries. Support for international cooperation can also be found at the highest levels of government.

In March 2022 at the Two Sessions (a pair of major political meetings in Beijing), Chief Designer of China’s Manned Space Program Zhou Jianping noted that China plans to welcome international astronauts to the Chinese Space Station after completion (to occur in late 2022). At the same time, Zhou called for more commercial involvement in China’s space sector more broadly. Separately, China’s 2021 Space White Paper—published in early 2022—called for more international cooperation across all fields, with the word international appearing 59 times (compared to “China”, which appeared 163 times). All things considered, we have a big market, and we have a fair amount of support for international collaboration. So far, so good. And yet, in China, it is never that simple, and complexity can make it difficult for foreign companies.

Perspectives on the Industry: The Bad, and the Ugly

Despite the large market and ample government support, Chinese commercial space is not an easy market to access. First, as already discussed, there are a lot of companies doing a lot of different things. This can be a good thing (large market), but can also be a bad thing: you probably have a competitor in China. And what’s more, probably the competitor is pricing their products lower than you are. Several times have we gone to China with a foreign product expecting to find much interest, and several times have we found competitors with price points that are half that of the foreign supplier. Space in China is much like most industries in China: competitive, and with a lower cost structure. But this is far from the only challenge.

Recent years have seen China become more serious about developing space technology domestically, which has created a strange contradiction. On the one hand, government and industry officials call for international cooperation, while on the other hand, they call for building more products at home. This means that for most space products that are low value in terms of technology, there is probably already a Chinese manufacturer. And for products that are more technologically advanced, there is probably at least one Chinese company working to develop them. And in many cases, there is significant support from local or provincial governments for specific sub-sectors, creating more competition in the most lucrative verticals.

In terms of industrial structure, the Chinese commercial space sector is limited by a combination of regulations, and attitudes towards said regulations. For example, in the United States, there are certain areas of space law or policy related to space that are unclear. And for many commercial space companies in the United States, the strategy is to ask for forgiveness, rather than asking for permission. In the Chinese context, the laws are equally unclear (if not even more unclear), but the culture around them is completely different: companies will ask for permission rather than asking for forgiveness. This means that commercial companies are limited in what they can do: for example, no commercial launch company is building a rocket that competes with the big state-owned rockets. It is impossible to imagine a Chinese commercial space CEO having the same disregard for the Chinese authorities that Elon Musk has for US authorities.

The Foreign Perspective: How to Work with China?

Different companies will have different strategies towards the Chinese market, but as foreign space companies, there are several avenues that may be worth exploring. For those developing very niche or specialized technologies, there is likely a market for your product, especially in the short-medium term before Chinese competitors catch up.

For companies building systems-level things (satellites), the opportunities may be considerably better, with China being viewed as a source for inexpensive and reliable space hardware. For companies looking to scale production, find R&D partners, or otherwise participate in product development with the potential for government subsidies, there are many opportunities. And for up-and-coming space-faring nations, understanding the development of the Chinese space sector can provide insights on best practices for industrial development, while also giving food for thought on how one’s national space industry can position itself relative to the Chinese.

At a civil space program level, countries with plans for human space travel or deep space exploration will likely find a willing partner in China. The country’s Belt and Road Spatial Information Corridor is bringing a variety of space infrastructure (remote sensing and comms satellites, among other things) to a country near you. And for universities or institutes looking for academic and research exchanges, there are dozens of major universities in China pursuing space technology and R&D. All this is to say, there is a lot going on in Chinese space, and there is openness to collaborate.

Specific examples include a recent announcement by China Rocket of commercial rideshare capacity available on their upcoming Jielong-3 launches later this year, multiple foreign collaborations with commercial satellite manufacturer Spacety (including Italy’s T4i and France’s ThrustMe). In the civil space program, China’s large-scale projects are opening doors for international partners, including the awarding of small amounts of Chang’e-5 lunar samples for research purposes.

Conclusion

Over the past couple of decades, China’s space industry has evolved into likely the world’s second-largest national space industry. With more than 200 commercial space companies and a state-owned space apparatus employing hundreds of thousands of people, only the United States has a space sector of a similar scale. The current state of US-China relations, however, means that these two large markets will remain largely separate.

For all other countries, relations with these two superpowers will be a delicate balancing act involving many trade-offs. Certainly not all western space companies will find a pot of gold in the Middle Kingdom. But in today’s rapidly growing space industry, China is a very important player, and whether your perspective on China is good, bad, or ugly, there’s a good chance it’s a market that’s too big to ignore.

---------------------------------------------------------

Blaine Curcio is Founder of Orbital Gateway Consulting (OGC), a research and consulting firm focused on the Chinese space industry. In this role, Blaine oversees a variety of research into Chinese commercial space industry fundraising, market sizing, industrial base development, and governmental policies, for clients including commercial space companies, governmental institutions, financial institutions, and consulting firms. OGC is building out the first comprehensive suite of Chinese space industry data points in a series of databases available to subscription clients. Based in Hong Kong, he maintains close relationships with the local space ecosystem in Asia-Pacific, including regular collaboration with the Asia Pacific Satellite Communications Council (APSCC) and the Hong Kong Orion Astropreneur Space Association (OASA). He is a Senior Affiliate Consultant with Euroconsult where he focuses on the global satcom industry, and is a regular moderator and contributor to the Euroconsult World Satellite Business Week. He can be reached at: blaine@orbitalgatewayconsulting.com

Aurélie Gilet, an associate of Orbital Gateway Consulting, provided some editing and research assistance for this article.

For the latest news and analysis on the China Space market, Blaine Curcio hosts a weekly podcast called Dongfang Hour. It can be viewed at: https://dongfanghour.com/