Many things have happened in the satcom industry in 2020. We as an industry have responded to Covid with a flurry of webinars, virtual conferences, LinkedIn posts, and an endless variety of podcasts. Meanwhile, satellite operators have been evolving, with 5G spectrum reallocation moving full steam ahead in some markets (including my home market of Hong Kong, one of the world’s leading assassins of C-band for satellite).

However, arguably the most significant event in 2020 has been the astonishing rate at which Starlink has launched LEO satellites. The company has now (29 November) launched 955 satellites, while at the same time coming to market with a “better than nothing Beta” product that is retailing for a fairly competitive US$499 + $99 per month. Meanwhile, the company has also signed a US$149 million contract with the Space Development Agency, among other agreements with the US military.

While the rapid ascent of Starlink has captivated media, politicians, and the space industry in the west, this is far from the only group—indeed, on the other side of the Pacific Ocean, the space industry as a whole, and most probably, the government in China have been watching Starlink with increasing interest. At the same time, there is an ecosystem developing in China around the country’s own LEO constellation projects, and while these projects are certainly not moving at the speed of Starlink, they are picking up major momentum and reaching considerable size and scope.

2020’s Changes in China LEO Policy

The most apparent policy decision by China this year was the inclusion of “satellite internet” on its “new infrastructures” list, published by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) in April 2020. The “new infrastructures” list includes a variety of infrastructure types that the government encourages private sector companies to develop. The inclusion of “satellite internet” has led to two main types of outcomes, one of which is policy-related, and the other business-related.

On the policy side, several Chinese provinces have since published relatively short-term (2020-2022, for example) “New Infrastructure Development Plans”. This has led to places such as Shanghai and Sichuan including “satellite internet” on their list of priority industries to develop in the 2020-2022 period. This will likely mean several things at a provincial/city level—faster government approval for space-related projects, increased government funding available for space-related projects, and increasingly large ecosystems of private Chinese companies in specific industries clustering in specific cities. One such example we have seen is a cluster of companies in Chengdu/Chongqing, in Southwestern China, seemingly supporting MacroNet, the operator of the Hongyan constellation. The second main outcome from the inclusion of satellite internet on the “new infrastructures” list was business-related.

From a business perspective, the inclusion of satellite internet on the “new infrastructures” list, likely accelerated by Starlink, has been significant. In the weeks after the addition, state-owned enterprises like China Telecom Satellite released several new satellite broadband products, utilizing GEO capacity and specifically mentioning the “satellite internet as a new infrastructure” in the product release. This was to be expected, insofar as state-owned enterprises tend to mobilize very quickly in response to government announcements of this nature.

Less directly related to the NDRC decisionn, but nonetheless very important for China’s future LEO constellation, is the “Space Ground Integration” initiative, a government initiative in China being run primarily by the China Electronics and Technology Group Corporation (CETC), and which picked up significant momentum in 2020. “Space Ground Integration” refers to the idea that there are an increasing number of space assets being launched—namely comms satellites, EO satellites, and navigation satellites—and that this infrastructure needs to be “better integrated” with the ground. This includes developing terminals, and all related electronic components for the terminals.

The Impact of Policy Changes on Businesses

In the more medium-term, the months after the NDRC announcement saw no less than 3 funding rounds highlighting satellite internet as “new infrastructure” as a major opportunity. Most notably, Galaxy Space is building a “superfactory” in Nantong City, Jiangsu Province, aiming to address broadband LEO constellations with a manufacturing output of 300-500 satellites per year. Noteworthily, Galaxy Space also completed a round of funding in November 2020, at which time the company specifically mentioned a goal of bringing the gap between China and the west in terms of smallsat mass manufacturing down to 2 years (the company also officially became a unicorn during that funding round, with a valuation of RMB 8 billion).

In the more medium-term, the months after the NDRC announcement saw no less than 3 funding rounds highlighting satellite internet as “new infrastructure” as a major opportunity. Most notably, Galaxy Space is building a “superfactory” in Nantong City, Jiangsu Province, aiming to address broadband LEO constellations with a manufacturing output of 300-500 satellites per year. Noteworthily, Galaxy Space also completed a round of funding in November 2020, at which time the company specifically mentioned a goal of bringing the gap between China and the west in terms of smallsat mass manufacturing down to 2 years (the company also officially became a unicorn during that funding round, with a valuation of RMB 8 billion).

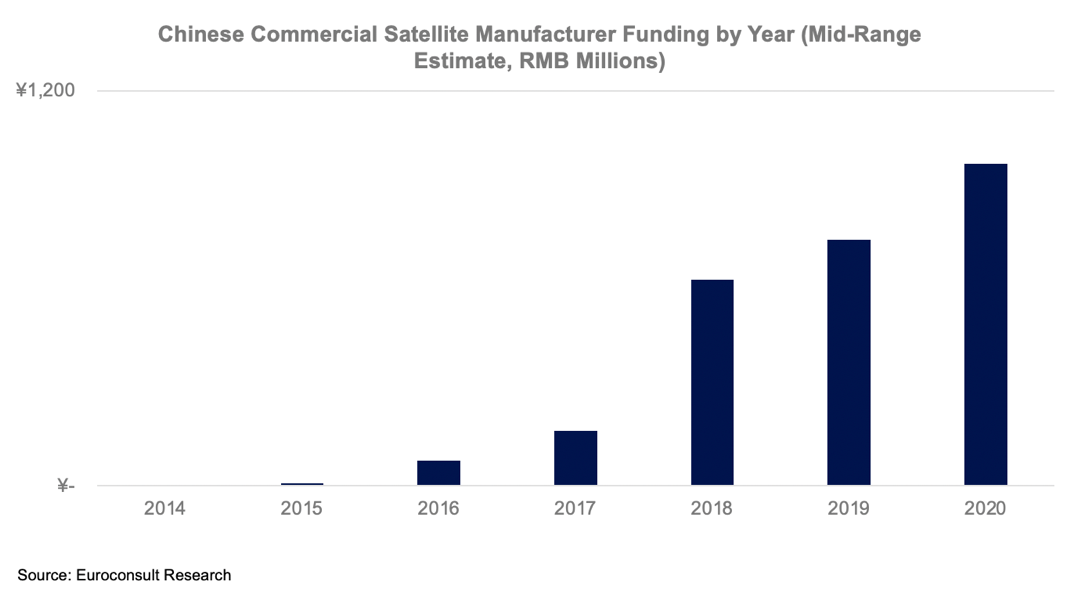

Commsat, another commercial satellite manufacturer, is building a factory in Yibin, and another in Tangshan, with the latter specified as aiming to have a production capacity of 100x satellites of over 100kg per year. CASIC subsidiary Space Engineering Development Company Limited has built a satellite factory in Wuhan also capable of producing ~100 satellites per year. Utilizing data from Euroconsult’s China Space Industry Report, we find that Chinese commercial satellite manufacturers have raised nearly RMB 1 billion in 2020 as a mid-range estimate, a record figure.

Overall, the policy changes of 2020 have seemingly given fuel to an already-burning fire. A satellite manufacturing industry that had raised nearly US$100 million per year in 2018 and 2019 saw a major increase in 2020 despite a pandemic, and several companies have made major strides in mass manufacturing of satellites, implicitly for a Chinese LEO constellation(s).

So What Will China’s LEO Constellation Rollout Look Like?

Moving forward, we are likely to see the development of at least one LEO broadband constellation from China, as well as likely a LEO

|

|

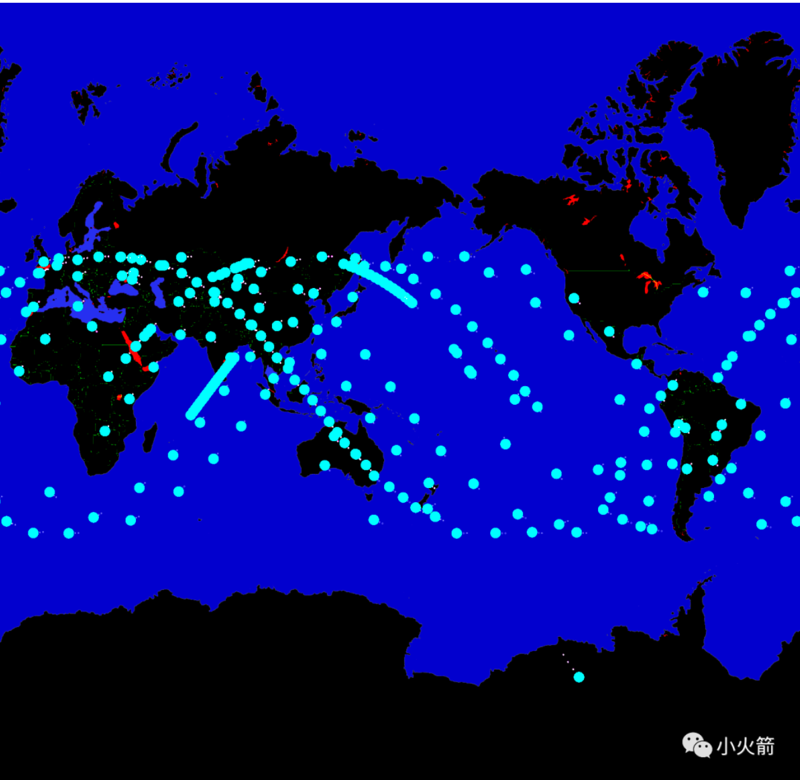

Artist’s rendition of China’s GW Constellation Source: Small Rocket, Toronto, Canada. |

narrowband constellation. China’s LEO broadband constellation plans have fallen into two broad categories—those spearheaded by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and those spearheaded by private/commercial companies. Broadly speaking, I believe that the former are much more likely to come to fruition as planned, insofar as LEO broadband constellations are basically ISPs from space—two industries that are very sensitive and usually state-controlled in China.

2020 has indeed seen a general pivot by private/commercial companies towards a stated goal of satellite manufacturing, as opposed to operating their own constellations. At the same time, we saw an apparently leaked document outlining a 13,000 satellite broadband constellation to be developed in 2 phases with 7 sub-constellations therein. The constellations are codenamed “GW”, with ITU filingns visible under such names as GW-1, GW-S, and GW. While not explicitly mentioned, the project would presumably be led by a state-owned enterprise. While it is admittedly speculation, it is also likely that the above-mentioned commercial companies that have pivoted towards satellite mass manufacturing would be given parts of this project.

Ultimately, we can likely assume that the development Chinese LEO broadband constellation would be primarily run by a state-owned enterprise or consortium thereof. CASC would likely manufacture a large percentage of the necessary satellites. However, despite recent increases in its satellite manufacturing output, CASC is unlikely to be able to manufacture 13,000 satellites by itself anytime soon—it will need help from commercial companies. In this regard, the handful of commercial smallsat manufacturers above are likely to contribute satellites.

The development of China’s LEO broadband network is likely to be far more “slow and steady” than Starlink. While the acceleration of Starlink has certainly led to acceleration in China, there is somewhat different calculus than, for instance, Europe. That is, if we take as a given that LEO broadband constellations could be a “strategically important piece of infrastructure” (a debatable point, but a given in this exercise), it could be argued that each major world space power (US, EU, China, debatably Russia) could justify their own constellation.

However, today, Starlink is seemingly far ahead of any EU competitor, while at the same time, because of the relative openness of the US and EU economies, Starlink may be able to start selling services in EU soon. Put simply, the future EU LEO broadband constellation could be killed before it is even born. On the other hand, there are precisely zero people in China who expect to use Starlink domestically in the coming years, there are no illusions that Starlink will get market access.

In this way, there is somewhat less impetus for China to throw everything at LEO in the short-term, because the market will remain closed. This concept would likely also apply in countries that are particularly close to China, such as Pakistan, Russia, etc.

What has 2020 taught us about China’s LEO Broadband Plans?

Overall, 2020 has taught us that China will likely launch its own LEO broadband megaconstellation. The aforementioned leaked document showing a plan for 13,000 satellites should be an indicator of the scale of these plans.

While it remains very likely that such a constellation would be managed by a SOE, the past year has seen several commercial satellite manufacturers pivot their business model from “we want to launch our own constellation” to “we want to build dozens or hundreds of satellites for some other constellation”. Several of these commercial companies have launched test satellites in 2020, most notably Galaxy Space in January.

2020 taught us several important things about the future Chinese LEO broadband constellation:

1. It will likely be a collaborative effort between SOEs and the private sector. Commercial satellite manufacturers are likely to build some of the satellites necessary to reach the >10,000 number we have seen.

2. Apparently, China is serious about its LEO efforts. The fact that the NDRC added satellite broadband to the list of new infrastructures, and the fact that several provincial governments have jumped onboard, has given the project significant weight. For perspective—Sichuan Province, which mentions satellite internet in its new infrastructure development roadmap for 2020-2022—is home to more than 80 million people and with an economy the size of Belgium or Austria.

3. While Starlink is likely to be an accelerant for the Chinese system due to a sort of “strategic competition” factor, it seems China will roll out its constellation at a relatively slow and steady pace. With a home market that will definitely not be at risk of letting Starlink in, and with many allies around the world that are likely to give China time to build its own constellation, the impetus has increased, but it remains measured.

4. Building a LEO constellation in China will likely be a fairly bureaucratic process. Not covered in this article as it did not occur in 2020, one only needs to look at the shareholder structure of MacroNet communications, the company that is tasked with operating the Hongyan constellation. Among its shareholders are CASC, the major state-owned space contractor, China Telecom, one of three titanic state-owned telcos, and China Electronics and Technology Group Corp, a state-owned electronics manufacturer. Basically, all three companies are huge oligopolists at best, and monopolists at worst. In short, there is limited overlap of incentives. China Telecom has several hundred million mobile subscribers, it is very hard to imagine a satellite broadband constellation making a meaningful impact on revenue. Likewise, CASC has its hands rather full with missions such as the China Large Modular Space Station, human plans for the Moon, and other space-focused missions that are clearly extremely difficult, but are, at the risk of oversimplification, probably far better-understood than LEO broadband. At the same time, we see in the west an incredible degree of vertical integration from companies like SpaceX and to some extent Kuiper. Probably there is a reason for this. When you are doing something so disruptive as providing a global ISP from space, there are a lot of vested interests that are going to be very hard to move.

Overall, 2020 has been a remarkable year in the satellite manufacturing industry in China. We have seen a major acceleration in fundraising, as well as a handful of LEO broadband test satellites launched by companies such as Galaxy Space.

---------------------------------------------------------

Blaine Curcio is the Founder of Orbital Gateway Consulting. He’s an expert on the commercial space and satellite industries with a focus on the Asia-Pacific region. He can be reached at: blaine@orbitalgatewayconsulting.com

For the latest news and analysis on the China Space market, Blaine Curcio hosts a weekly podcast called Dongfang Hour. It can be viewed at: https://dongfanghour.com/