29 August the long-anticipated launch of the Artemis-1 SLS launch vehicle was postponed at countdown T-40 minutes due to an engine coolant problem. This must have been disappointing not only for NASA and ESA (which developed the Artemis program Orion spacecraft Service Module) but to the millions who were looking forward to the spectacle of the most powerful launcher ever blasting-off, signaling the beginnings of the human return to space beyond the low Earth orbit of the ISS, and in preparation for a new generation of Moon landings… and more. At the time of writing the lofting of the SLS has been re-scheduled to Saturday 3 September… Fingers crossed all goes well!

Why is this important for the satellite communications and wider space industry? Let’s examine the situation, including how it relates to what the industry must do to recruit, “onboard”, and retain human talent.

Space Ages

The first Space Age – Space 1.0 – was met with awe, enthusiasm and wonder, with the world witness to the superpowers’ space race, human footprints on the Moon, the Space Shuttle program, and the construction of the ISS. The question is, “Will the sight of a launcher more powerful than the iconic Saturn V ascending to space re-kindle a general fascination with, and understanding of, the realms of space and satellite?”

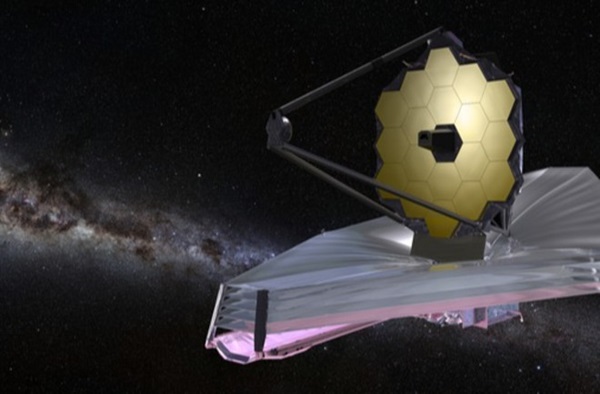

Of course, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has recently contributed to making the subject of space widely topical again. Publication

|

| James Webb Space Telescope |

of the first images from the JWST – more profoundly revealing than those of the ageing Hubble Telescope, and showing detail of the Universe to almost within the first 100-250 million years following the Big Bang, which is almost as far back as the Universe before the formation of stars, and comprising only a sub-atomic particle soup – has impacted the public consciousness.

However, against this background, what is important is understanding that whether we are extending the boundaries of our cosmological understanding, or realizing what humans can achieve and discover in orbital micro-gravity, or are preparing for a return to the Moon and, one day, continuing to Mars, these examples offer the general populace only the smallest of clues about what space means to the human race.

To understand what space does mean to humanity we don’t need to look back in time to the extremes of the Universe’s beginning. We can look much closer to home; between the Karmen line and the geostationary orbital arc. This is Earth’s useful orbital space. Levels of general awareness of its significance to everyday life is limited.

Now, the first Space Age has yielded to the second Space Age, or Space 2.0, but midway we have been through what I like to consider as Space 1.5.

Of course, the Artemis program is but one facet of Space 2.0, and much has been written about the wide entirety of NewSpace – radically altering both space segment and ground segment – but whilst we in the space and satellite industries continue to be excited about this new era, also described as the “industrialization of space”, wider appreciation by the broader populace is limited.

The Value of Space

A recent report commissioned by Inmarsat is illuminating here. The research – published as ‘What on Earth is the Value of Space?’ – is based on the most in-depth research ever carried out on global perceptions of space: 20,000 respondents; 11 countries; and a demographic featuring different cultures, different age cohorts, and differences between business leaders and the general public. The Report offers ample illustration that people generally do not appear to understand the role space is now playing in their everyday lives.

My own question to a similar demographic would be, “What Does Space Mean to You?” If the response was akin to that highlighted by the Inmarsat-commissioned research, there is much reason for our industry to be concerned that perceptions of space are rather more shaped by popular entertainment genres – being associated with ‘Star Wars’ by 10 per cent of Inmarsat’s respondents, associated with ‘communications & connectivity’ by only 8 per cent, and associated with ‘broadcasting & television’ by just 3 per cent – with the real-world technologies and services provided by space and satellite being seemingly invisible to most.

While the older demographic not only had direct experience of Space 1.0, they tend to appreciate the technology off-shoots of that period which have contributed to improving life on Earth. The younger demographic takes such improvements for granted, and when it comes to their understanding of Space 2.0, they are more likely to reel-off the names of certain famous billionaires sending cars and tourists to space rather than anything rather more related to the lives of ordinary people.

This suggests that the era that, as noted above, I think of as Space 1.5 – the age of the birth and growth of geostationary satellites delivering broadcast video and data, and of millions of VSATs around the world delivering myriad services for commerce, consumers, enterprise, and government – has grown more or less under-appreciated by the majority. The widely anticipated launch of the SLS would be seen in quite a different light if the public knew, for example, about the number of commercial communication satellites launched year-on-year over recent decades – using launch vehicles from multiple manufacturers, using launch sites in multiple countries – and this before the advent of re-usable launch vehicles and satellite multiple launch dispensers for NGSO.

Aside from any other considerations about the desirability of having greater visibility for the commercial satellite industry, there is the question of the industry’s “human factor” – its human resource base, its pool of available human experience and knowledge. Beyond the technology, behind the services, there must be the skills of trained human beings, people who have to be attracted to careers in space (without actually going to space).

Skills and Certification

The Space Skills Alliance, with which GVF has previously collaborated on issues pertaining to space skills, is a UK-based organization with roles as a ‘think tank’ (helping policy-making process by publishing reports), a consultancy (providing expert advice to organizations looking to improve their skills pipelines), and a backbone organization (enabling collaboration and improving the way organizations in the space sector work together to address common skills challenges). Aside from other functions, the Alliance produces a Space Training Catalogue, a free directory of training opportunities for the UK and European space sectors from astrobiology to additive manufacturing, remote sensing to rocket launching, and space medicine to spacecraft operations. The Catalogue has long-featured courses comprising the portfolio of GVF’s technical training, but now also features the non-technical training of the SBQ.

As previously described in this column, GVF – and its partners, SatProf and the SSPI – have developed a series of Space Business Qualified (SBQ) Fundamentals courses as the first part of a comprehensive solution to the recruitment, “onboarding”, and retention needs of the space and satellite industry. The SBQ program provides a comprehensive understanding of the business of space today and tomorrow through a set of online courses and certification ideal for people new to the space and satellite industry or for those already on the “inside” of the industry wanting to deepen their knowledge.

Recently made available for immediate enrollment is SBQ405: Space Business – Finance, Legal & Regulatory, the fifth and final course in the Fundamentals series following SBQ401: Fundamentals of Orbits and Getting into Space; SBQ402: Spacecraft Fundamentals; SBQ403: Space Communications Fundamentals; and SBQ404: Space Business – Markets. Each course can be separately purchased, or the discounted Fundamentals Certification Bundle, which includes SBQ401 through to SBQ405, can be purchased. (See… for more details.)

Additional courses are already being developed. Following on from the Fundamentals courses will be more specialized courses in satellite communications, earth observation and spacecraft and launch.

Watching the launch of the Artemis-1 SLS will be children born after the last Space Shuttle program flight by the orbiter ‘Atlantis’, 11-years-ago. Among those children will be the potential future generation of space and satellite industry employees. Their S.T.E.M. education will be the start of their technical/engineering careers in space and satellite. Alternatively, their liberal arts education can be supplemented by SBQ as their route into, for example, business development or satellite sales and marketing, etc.

Those children will have their parents watching with them, perhaps from far away on TV, or perhaps they will have been excited enough by space to have traveled hundreds or thousands of miles to Cape Canaveral. Most of those parents will be employed in jobs which are not space-related, but they may exhibit certain skills that space and satellite companies value and need. Their key to transitioning to a job in a space-related organization can be the knowledge and comprehensive understanding of the business of space today and tomorrow that pursuing SBQ provides. If those parents are already employed in the space industry, they may need to enhance their knowledge base, and SBQ provides the opportunity for this too.

We know that the space and satellite industry must recruit more talent, now. We can reasonably assume that this need will grow and grow over time. SBQ is the present and future solution for “Mastering the Business of Space”.

-------------------------------------

Martin Jarrold is Vice-President of International Program Development of GVF. He can be reached at: martin.jarold@gvf.org

Martin Jarrold is Vice-President of International Program Development of GVF. He can be reached at: martin.jarold@gvf.org